I majored in history and political science, so how to research was a key part of my success in writing papers, essays, and so on. Add in I almost had a minor in English, and being able to support my premise in writing became second-nature to me.

This is something I was able to use well in my work at the FAA. No matter the topic I was assigned to write about, be it technical, policy, regulatory, or historical, I knew how to research and back up what I’d written with facts. Some of the time the editor accepted what I’d prepared. However, if it conflicted with the way he thought things were, he’d change it and make the article incorrect from a technical viewpoint. When our technical experts would point that out to him, he’d relent because they were, well, mostly men. There was a positive outcome for my years as a reporter working for him though. When I eventually became the editor, I knew exactly how I wasn’t going to treat my reporters.

But I digress.

Again, when I had to prepare answers to congressional questions, I was so practiced at research that my turn-around times and the accuracy made the bosses really happy. All this because in high school and college I learned those research skills as well as not taking a single source as the correct or only information. At my college, the history department insisted upon at least three original sources to back up a conclusion in a paper. In aviation, sometimes a single source was all I had, i.e., the regulations, but habits die hard. I’d also interview an expert on what I was writing about and consulted policy documents and past white papers on the subject.

So, come 2009 and retirement eligibility. I knew I was retiring to write for myself. I knew what I was going to write—historical fiction and spies. Because I’d never been a spy, that meant my research skills had to be put to good use.

I was confident. I knew how to do this.

At the FAA, I had access to an extensive aviation library and its erudite librarian. I’d tell him what I was working on, and he would return with a stack of books, some of them so rare that I had to don the white gloves to open them, and he hovered to make sure I didn’t bend any book spines.

Another aside. Over the years as the FAA headquarters building needed more space, the aviation library was reduced in size multiple times. The rare books went to the Smithsonian, and other material was digitized and . . . Well, I really don’t want to know the disposition of the original material.

In my retired life, I do have access to public libraries, even a university library since my alma mater is just up the road from me. However, public and university libraries often contain general information, lots of it, and librarians are way too busy to focus a lot of time on a single patron.

That meant I was left with the Google and its predecessors. In late 2009 when I retired, Google was a bit over a decade old, and I’d used it, Yahoo! Search, AOL, Ask Jeeves, and a lot of other not so well known search engines in the 1990s for work and for personal use.

Google has only improved over the years and is one of perhaps even the most popular search engine for research.

And that may be the problem.

Let’s say, I’m in the middle of a scene and I want to confirm whether a piece of technology was available, in, say, 1990. I’m not one of those writers who can make a note to go back and check later. I can’t continue the scene until I know for sure.

I head to Google (mainly because I use Chrome as my browser). The first hit I get is usually a Wikipedia article on the subject. Now, using Wikipedia as your only source for confirming information for historical fiction can result in embarrassing errors, but it’s a good starting place. However, even for confirming dates, I go beyond Wikipedia, to a company resource or a scholarly article online. Much the way I researched in college with stacks of books piled on my work table in the library.

Indeed, to find out when Google first appeared . . . I Googled it.

However, the online part . . .

It’s so much easier to click on a link than to search through a book, and those links can be fascinating. They may only bear the slightest connection to the subject matter I’m researching, but for a history nerd, they are a big temptation.

Writers call it going down rabbit holes, and I’ve gone down a lot of them. All of a sudden, that tiny tidbit of info you wanted to confirm quickly has turned into a two-hour dive into interesting information, even if it’s ultimately useless to your plot. It’s like a kid with unlimited funds in a candy store. You want to try all the candy.

But . . . It is fun and you end up with all sorts of trivia that never makes it into your novel, but you can put it to good use at your local bar’s trivia night.

Don’t skip your research if you write historical fiction. Trust me, you don’t want a message from a reader explaining in excruciating detail what you got wrong.

Those rabbit holes may tempt you like Alice, but have a little discipline.

Yeah, not happening.

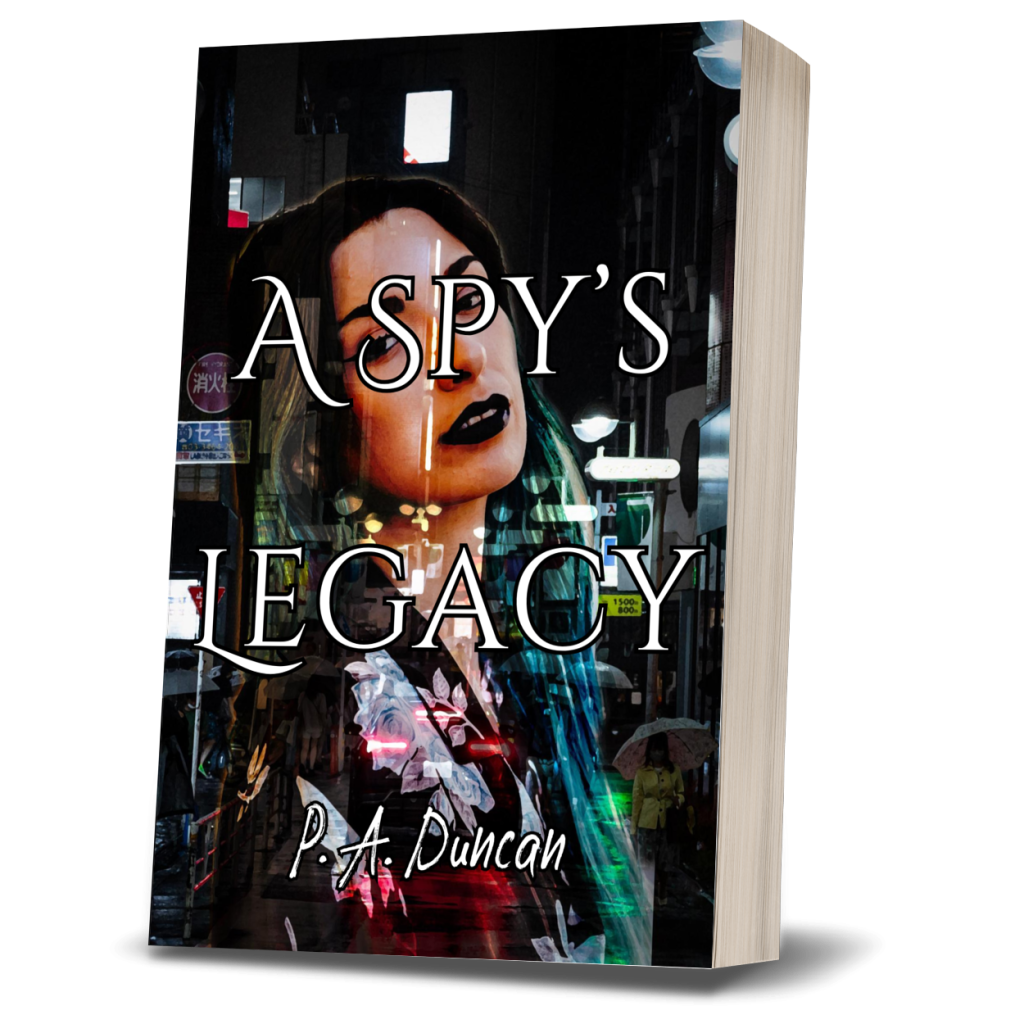

A Spy’s Legacy

This past Saturday, June 15, the print edition of A Spy’s Legacy, book one in the eBook box set SECRETS, went live as a paperback.

A Spy’s Legacy is available from Amazon for $16.99 for the paperback. Paperbacks of books two and three of SECRETS will come out in July and August, respectively.

By the way, the title, A Spy’s Legacy, is an homage to one of John le Carre’s last books, A Legacy of Spies, which is a sequel of sorts to his most famous and my favorite novel, The Spy Who Came in from the Cold.

Though he was unaware of it, I considered le Carre my role model, even mentor, in how to write realistic spy fiction.